The Elf Society: Fifteen Years of Quiet Magic at Centennial

The Elf Society: Fifteen Years of Quiet Magic at Centennial

By Tyler Dahlgren

Kathy Calder does not think of herself as an elf. Not in the traditional, jolly and jovial sense, anyway.

She is more likely to describe herself as a straight-shooter, a tough cookie if you will. By Calder’s own admission, her personality aligns more with the Grinch’s than it does with Buddy the Elf’s.

“I can be a hard case,” Calder said. “I have rules and expectations for my students, even if I’m subbing, and I expect them to follow those rules and to meet those expectations.”

For 55 years, Calder’s students have known exactly where they stand. Part of the last graduating class from Utica High School in 1967, Calder spent 40 years as Centennial’s athletic trainer. She’s a constant in the district, a true Bronco through and through.

“She’s been taking care of kids for a long time,” said Centennial Elementary principal Brad Luce, a 2006 graduate of Centennial himself. “Everybody knows Kathy.”

For the past 15 years, Calder has quietly led one of the most meaningful traditions in the district, providing food, winter clothing and toys to more than a thousand children who might otherwise go without. It’s called The Elf Society, and, believe it or not, Calder, the self-described quasi-curmudgeon, is the lead orchestrator.

It’s a windy December morning in Utica. Christmas is right around the corner, and Calder sits in the office of Centennial Public School and waits for an interview that Luce never thought would happen.

“If you’re from here, you’ve probably had Kathy as a sub, or she treated you for a sports injury, or you know her from the swimming pool or you’ve been impacted in some shape or form by The Elf Society,” Luce said of Calder, who also managed the city swimming pool for four decades. “But I don't think people always know that that's where it's coming from, because she's so humble about it and does not want credit. I didn't think she would ever go for this.”

The Elf Society doesn’t announce itself with fanfare. There are no names released, no photos shared, no expectation of recognition. It’s a miracle in the background, offering the kind of anonymous assistance that matters when a family is facing a hard season and a child is sitting in a classroom, listening to classmates talk about Christmas lists they know will never be theirs.

“Somebody has to fix it,” Calder said simply.

So that’s what she did.

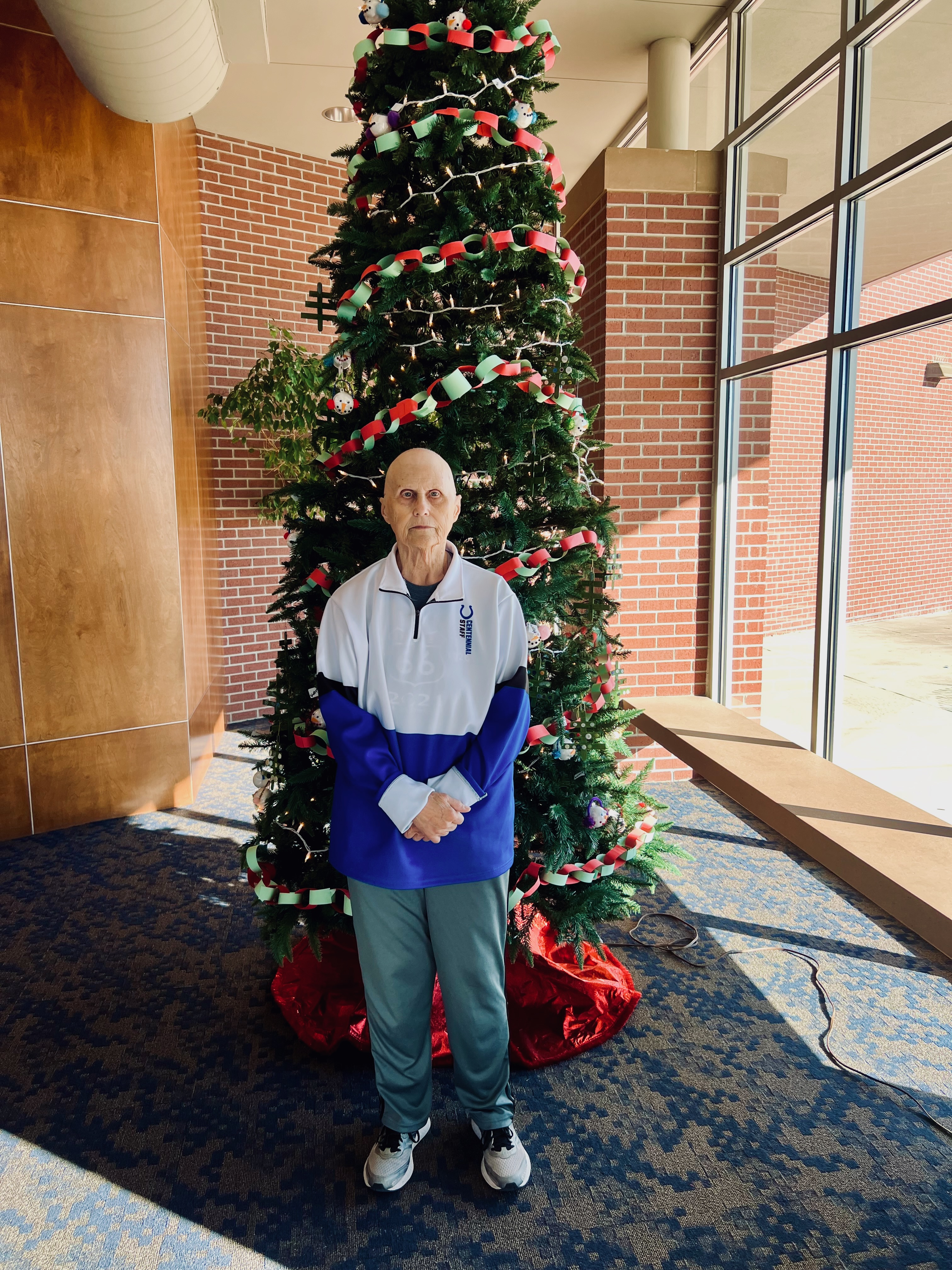

Calder doesn’t tell the story often, but we were in luck last week, when we sat down with Centennial’s lead elf. Calder, who recently finished chemotherapy for stage-four cancer, was as matter–of-fact as advertised. She was also more spirited than she might like to admit.

“It’s hard to put into words what Kathy means to Centennial,” said superintendent Seth Ford. “She’s just one of those people in our small rural community that just steps in and fills the gap. Whenever there’s something that needs to be done, she does it.”

I turn the recorder on, and we’re off.

“Fire away, Mr. Dahlgren.”

The Elf Society began not as a program, but as a response. One of those gaps needed to be filled, and Calder was in the right place at the right time.

Fifteen years ago, Calder was substitute teaching in a resource classroom when she noticed a third-grade boy who refused to participate. He sat in the corner, arms crossed, glaring through the lesson. Day after day, nothing changed. Other kids eagerly counted down the days to Christmas break. This one didn’t.

So she asked the school counselor what was going on. Christmas was coming, the counselor explained, and this child’s family had nothing. Less than nothing, actually. No presents under the tree. Barely enough food. His siblings were facing the same reality.

“He’s listening to other kids talk about what they’re going to get,” Calder recalled. “And he knows they’ll get nothing.”

Her response was blunt.

“I’ll fix it.”

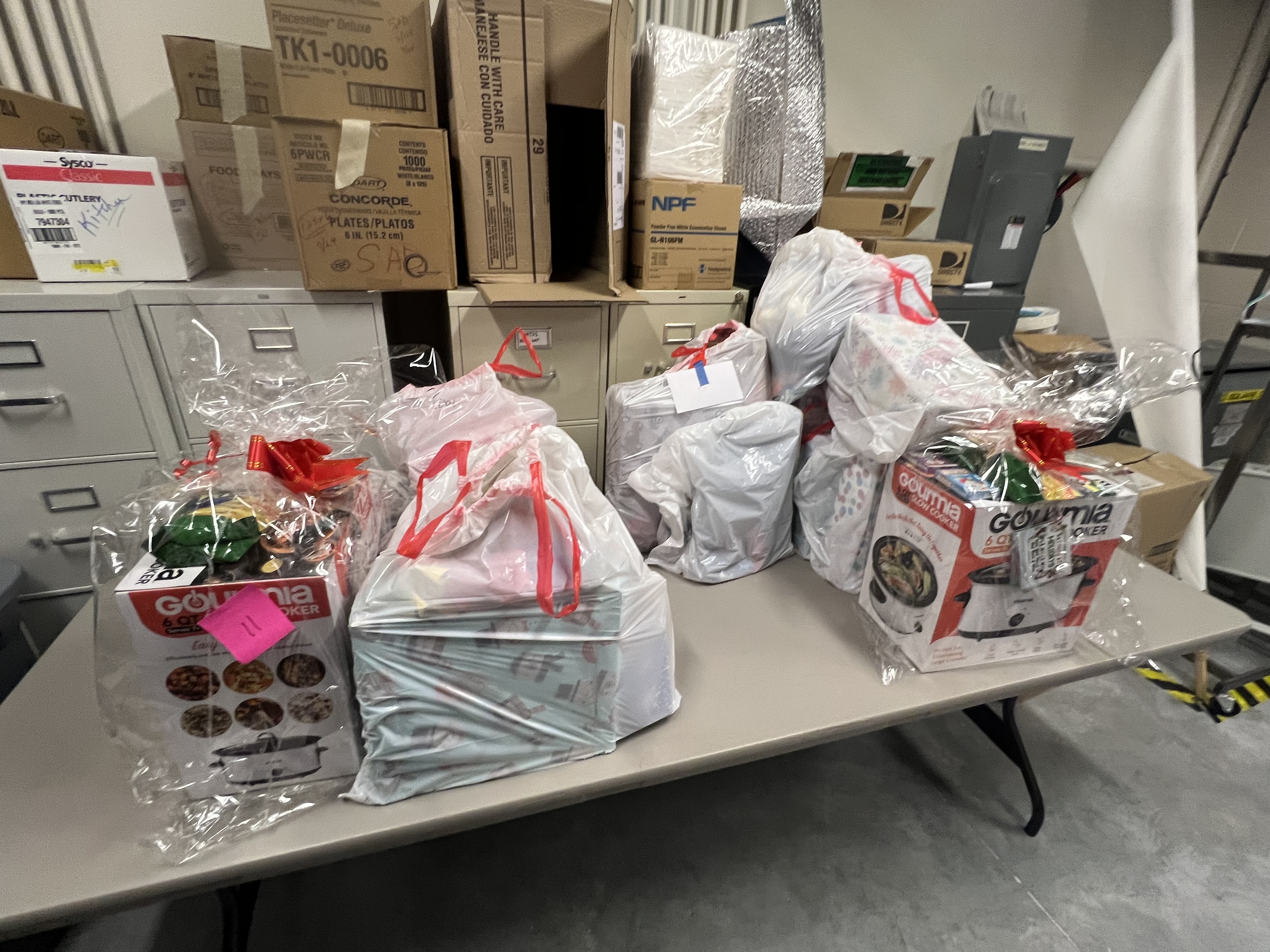

Calder called a few “nice people.”. They went shopping. Then more relatives moved into the home. Calder called more “nice people.” They went shopping again. Each child received winter clothing, toys they could enjoy alone and share with others, and a family game, something that created togetherness and not just a distraction.

The following year, the counselor returned. There were more children in need. Calder was ready.

“I’ll fix it.”

The numbers grew, from four children to eight to 17 to 20, and so did the organization behind the effort. What began as a one-time act of kindness became a structured, confidential system designed to protect dignity as much as it provided help.

Today, the Elf Society is carefully coordinated through Centennial Elementary. Teachers and staff nominate students, the elementary counselor contacts families to ask if they’re willing to accept help, and only a small group of people ever know who receives assistance.

The volunteers are coined elves and shop anonymously. They receive an envelope with clothing sizes, favorite colors, and a short wish list. Each child is allotted a set amount of money. Gifts are wrapped, labeled only with names, and returned to the school.

“Unless you happen to recognize an unusual name, you don’t know who you shopped for,” Calder said. “That’s important.”

Since that first Christmas in 2010, the Elf Society has raised over $100,000 and helped an estimated 1,000 children across Centennial’s communities. Some families have been served more than once. Support extends beyond Christmas, too. Calder’s team has covered sports fees, swim passes, or emergency clothing when needed.

Principals are even given a small discretionary fund so they can respond immediately when a child needs shoes, a coat, or a sweatshirt. There’s no need to navigate any red tape.

“It’s help that meets people where they are,” said Luce. “And it happens because Kathy saw a need and stepped up.”

For Luce, The Elf Society reflects something deeper than seasonal generosity.

“It encapsulates who our communities are,” he said. “They wrap their arms around people. They don’t ask questions. They just help.”

Staff members volunteer year after year, shopping and wrapping gifts alongside community members and local businesses. Trust, Calder said, is what makes it all possible.

“I can’t believe people just hand me money,” she admitted. “And someone told me, ‘They trusted you with their kids for decades. Why wouldn’t they trust you now?’”

Calder has gone 50 years without softening her approach. She’s known for holding students to high expectations. for being fair, firm and consistent.

“I was hard on you kids,” she once told a former student.

“But we always knew where we stood,” the student, all grown up by then, replied.

Pulling off the magic was no picnic this year. The economy made fundraising harder, Calder explained. And chemotherapy treatment is the furthest thing from fun. Still, she pressed on.

“I started earlier this year,” she said. “We scrambled a bit, but we made it.”

After returning to school following treatment, Calder spoke directly to students. She answered questions, explained changes and, staying true to form, she was completely transparent and honest.

“If it’s a distraction, I’ll wear a hat,” she told them. “Otherwise, what you see is what you get.”

With Calder, it always has been. She’ll never truly know the impact she’s made on this small community between Seward and York off Highway 34, and the odds are slim she’d bask in it much even if she did. But when the holidays arrive each year, Calder does look forward to a simple thought.

It’s one that always brings her peace.

“On Christmas morning, I get to wake up and know that there are a bunch of people having a better day today.”

The Elf Society has brought happiness to children for 15 years. It’s a well-known Centennial secret just who it is behind all of the magic.

After all, an elf with an edge is an elf all the same.