Mr Friend, Mr. Freeman: The 60-year story of an Omaha principal with a fascinating past

Mr Friend, Mr. Freeman: The 60-year story of an Omaha principal with a fascinating past

By Tyler Dahlgren

I can close my eyes and make 30 years disappear.

It's Field Day at Prairie Wind Elementary in northwest Omaha, late spring of '96. For us kindergarten kids, this was the Super Bowl. We dreamed of eternal glory at the potato sack race finish line and of the everlasting fame that would come with winning the baseball long toss.

It was a hot day, by May's standards, and the hallway was busy with rowdy six-year-olds, sunglasses and sunscreen bottles. I'd long-since mastered the art of shoe-tying, becoming something of an expert in the craft of looping, swooping and pulling by then. Unfortunately, on this, the most important day of the year, I encountered the Hercules of shoestring knots. The final boss, you could say.

No matter what I did, I couldn't crack the code. My classmates were heading outside. Time was running out. Those gold medals were slipping through my grasp. I fell into a panic.

Then I saw a dress shoe, followed by a knee, a hand on the shoulder, and a smile. It was my principal, Mr. Freeman, a beloved joy of a man who had untangled knots far superior to this in his 30 prior years working as a teacher and an administrator in Omaha Public Schools. My Field Day went off without a hitch, and I had myself a core memory.

I've been writing these stories since 2016, and I'm always on the lookout for good leads. This one took me home, to that elementary school just north of 108th and Fort, where our principal was more than just a core memory. To a bunch of five, six, seven and eight-year-old kids, Mr. Freeman was a friend.

We met for lunch yesterday, the first time I'd seen my elementary principal in 27 years. I turned on a recorder and Mr. Freeman told me about his life, stopping several times to ask me about mine.

I asked Mr. Freeman if those little moments mean as much to him now as they did to us then.

“Without a doubt, those little things become memories that you never forget,” he said. “The smile that the kid might have on his face, you don’t forget that. Those little things end up meaning so much.”

Sixty years ago, before he made his way to Nebraska as a part of the first ever National Teacher Corps class and before he left an imprint on the hearts of thousands of kids in Omaha, James Freeman marched in Montgomery to Selma, alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and John Lewis.

James Freeman has never shied away from asking questions. His curiosity has always served him well.

His heart has served Omaha well, too.

This is his story.

Mr. Freeman can close his eyes and make time disappear, too.

Born the son of a sharecropper and a housekeeper, he grew up in Colbert, a small farming town 12 miles east of Athens, Georgia. Schools were segregated, it being the 1940s and 50s, and, even as a youngster, Jim wondered often, ‘Why?’

“The population of our little town was about 800, and that included all the cats and dogs,” he said with a chuckle. “Most of the black kids weren't able to attend school during harvesting season, August through November, unless it rained, because they had to be in the cotton fields picking cotton, however, all the teachers had to be there every day. My father knew that, and being the wise man he was, he told my brother and I,we were going to school every day to receive almost one-on-one instruction from morning to noon, then we’d work in the cotton fields from noon to dusk. My brother and I and a few more students had perfect attendance, attending school a half day during harvesting season and receiving one-on-one instruction.”

Teachers in Colbert learned quickly that the curious kid showing up every morning to dive into tattered secondhand textbooks was pretty smart. Freeman says he didn’t know at the time whether he was smart or not, but he was dead set on finding out.

A standout basketball player by the time he reached high school, Freeman put a little spending money in his pockets by landscaping and taking care of yards around town. One of those yards belonged to an instructor from the University of Georgia. The two got to talking one day.

“He said, ‘Jim, you’re a smart young man, have you thought about college?’” said Freeman. “I said, ‘What, are you kidding me? I don’t know anything about college. I don’t have any money to go to college.’”

The professor encouraged Freeman to meet with a counselor at school about attending college. That meeting came to an abrupt end when the counselor at school affirmed Freeman’s sentiment.

“You can’t afford to go to college,” he told James.

Freeman returned to the professor, disencouraged but not dejected. The professor pried on, urging Freeman to send a letter to Tuskegee University, a school in Alabama made famous by the likes of Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver. Freeman was accepted and given a scholarship, but even that wasn’t enough to convince his high school counselor that he was college material.

“He called Tuskegee and said I wasn’t ready,” Freeman said, his eyes flickering at the thought of a challenge, even all these years later.

That counselor had no idea.

With flying colors, Freeman passed a test sent by Tuskegee.

He was accepted and could enroll, but his scholarship had been given to someone else. The only scholarship available was through the Opportunity Scholarship Program Plan, a five-year plan where you were required to work full time the first year while attending school part time before working part time and attending school full time for four years. So, he worked. His first year at Tuskegee, he worked full time as a custodian at the elementary school on campus, Chambliss Children House. The next four years, he worked part time on the yearbook staff and the campus newspaper staff.

“That’s how I got into school, that five year plan that included working part-time,” he said. “And then, moving forward, that’s how I got involved in Civil Rights.”

The early to mid-1960s were the best and worst of times, said Freeman, He became a part of the Tuskegee Institute Community Education Program (TICEP), launched by Tuskegee University to address educational and social needs in the Black Belt regions of Alabama. Freeman went from doorstep to doorstep encouraging people to register to vote. That’s when he first crossed paths with Martin Luther King Jr.

“What really touched me about the Civil Rights Movement was the number of people we became involved with,” he said. “And it was people of all colors. There’s this perception that it was just black people. No, no. You talk about the number of white kids, the number of Hispanics, it was a melting pot of everybody, and the relationships we built with those kids were strong, because they didn’t have to be there.”

Any real change that has been made throughout history, Freeman said, was spurred on by young people. He realized that then, in the moment, and perhaps it’s what turned his compass towards education.

“All those changes could only be made by young people, because they have the fortitude,” he said. “They’re not afraid, and they think beyond. I think that’s what made the difference in my life, the young people I was involved with, people of all different colors and backgrounds, from all over the country.”

In the years before Freeman’s arrival, Tuskegee had grown a little complacent. Then a young new Dean of Students, Dr. “Dean” P. Bertrand Phillips, came and infused the campus with energy. He emphasized to Tuskegee students the importance of getting involved, and did they ever. Freeman marched alongside King from Selma to Montgomery and all over the state of Alabama.

“With Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., you felt you could conquer the world with nothing,” Freeman said. “Everything was nonviolent, all the time. That’s the only thing we could do, overcome and keep on fighting the fight, and that’s what we did.”

James Freeman had no intention whatsoever of spending any of his life in Omaha, Nebraska. He’s honest about that, even after 59 wonderful years in The Heartland.

A senior at Tuskegee, Freeman was sitting in a philosophy class when his professor, a Dr. Eubank, came in waving an application to be a part of the National Teacher Corps inaugural class. The NTC, launched in 1965, aimed to train teachers for low-income areas.

There were 50 or so students in the class, but Dr. Eubank zoned in on one.

“He said, ‘Jim, I have an application here. You can go anywhere in the country and earn your master’s degree, receive a teacher’s salary, but you don’t want to do that. All you want to do is get you a red GT and have yourself a good time,’” said Freeman, his posture changing again recalling another life-changing challenge. “I said, ‘Give me the application.’”

He filled it out, and, a couple days before graduation, received a call from Dr. Floyd T. Waterman, a professor at Omaha University. Dr. Waterman wanted Freeman to come to Nebraska as part of the NTC’s first class. Freeman, however, wasn’t thrilled with the idea, so he and a friend paid a Friday night visit to Dr. Eubank, who lived near campus.

“We got accepted to Omaha, but we’re not going,” the pair proclaimed. “He said, ‘You’re going.’ We said, ‘No, we’re not.’ He said, ‘Yes, you are. Be at the airport tomorrow morning. I’m sending you both first class to Omaha.’ My friend, Sam Crawford, said, ‘Let’s go, stay two years and come back.’

The first flight Freeman took in his life brought him to Eppley Airfield, where he was greeted by Dr. Waterman and administration from Omaha University. It was a hot day in June, the College World Series was going on, and the cab’s air conditioning was laboring to keep up.

As the cohort rolled down North Omaha’s 30th Street, Freeman started noticing “For Sale” sign after “For Sale” sign. What is going on? He asked himself that question first, in his head, and then he said it out loud.

“Well, a black family moved in and everybody started moving out,” answered the cabbie.

Freeman breathed deeply.

“My goodness,” he said, “I’m just leaving the South and I’m coming here for this, what have I been fighting for this whole time?”

The young educator stepped into the classroom, determined to make a difference. Freeman thought he'd be here for two years, tops. Then he got to know the community, began building one of his own.

Perhaps he'd make a home out of this place yet.

Freeman came to Omaha with purpose. In teaching, he found passion.

His first position was teaching sixth-graders at Conestoga, a school just west of Carter Lake that employed some of the best teachers he’s ever spent time around.

“They sort of took me under their wing and showed me everything,” Freeman said. “I didn’t always know what I was doing in those early years, but I was determined to make each one of those kids a better person.”

Even as a young educator, Freeman was unafraid of outside-of-the-box thinking. The seating arrangement for his students was always strategic, placing the high-achievers next to the kids who needed a little extra help. Nobody knew that was on purpose, but every last detail in Mr. Freeman’s classroom was calculated.

“I wanted them to take responsibility, and, at the same time, I wanted them to help each other,” he said. “I’m telling you right now, students can teach students. Once you give them the concept, one student can teach another effectively. I knew they could help each other. I knew what I was doing.”

Students began to flourish. Before long, Freeman’s famous “Fruit Hour” was born.

“They could bring their fruit and their chips and when the clock struck three o’clock each day we’d stop what we were doing, and we’d eat and talk about the day,” Freeman said. “I see former students all the time, and they still talk about that. It was the best thing for them. We’d work hard all day, but the last 30 minutes was Fruit Hour.”

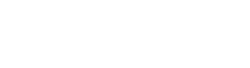

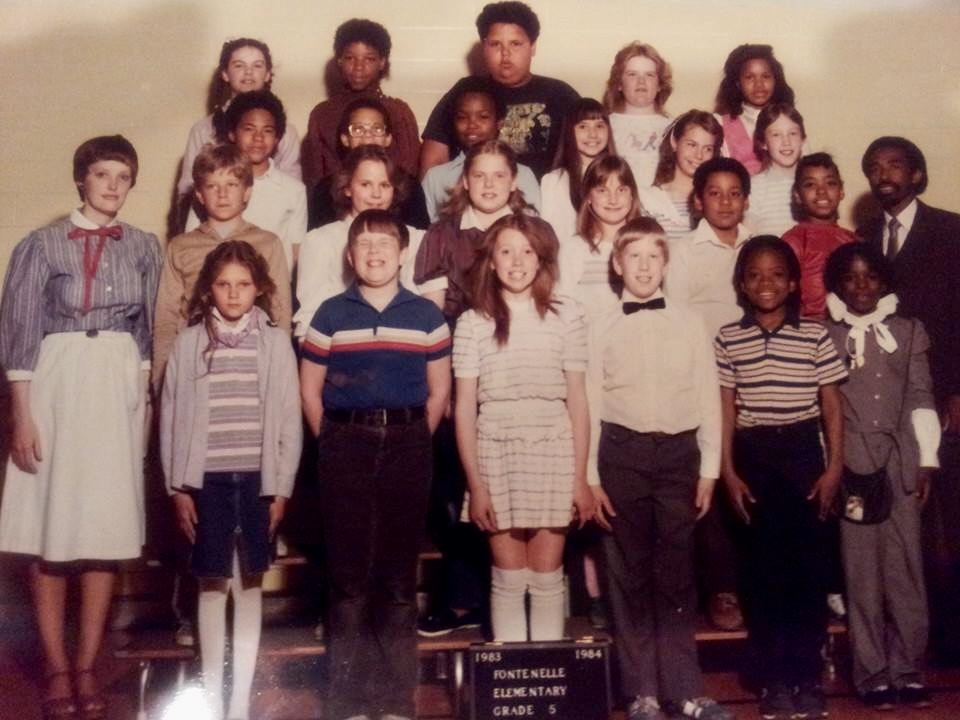

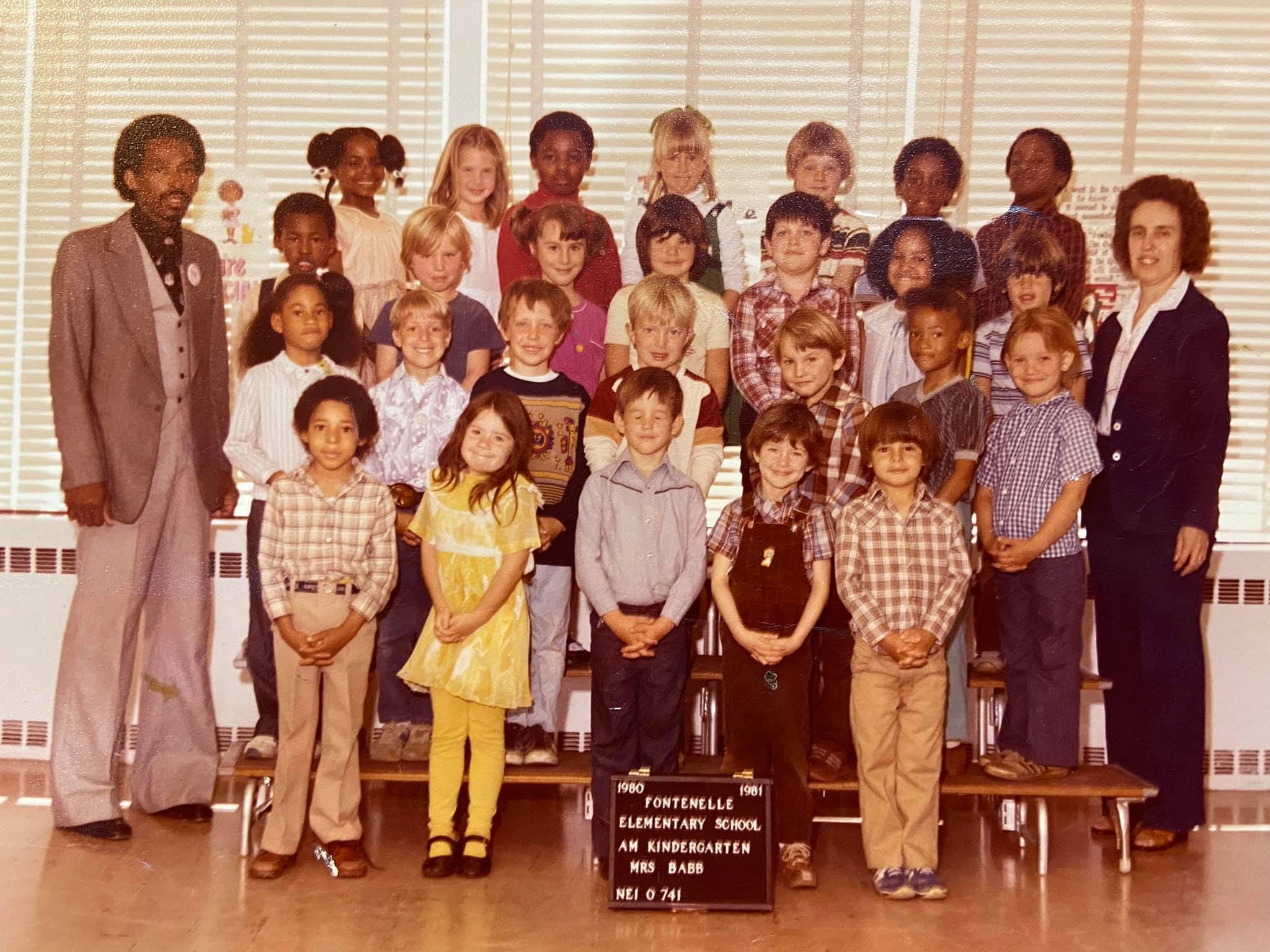

The NTC program had trained its first class to ingrain themselves in their surrounding community. In North Omaha, Freeman found that practice to be worthwhile. He took the jump into administration after a couple of years, serving as assistant principal at Saratoga Elementary and then principal of Druid Hill Elementary, Martin Luther King Middle School, Fontenelle Elementary and then Prairie Wind Elementary. At each stop, Freeman invited parents and families to be a key cog in the school’s everyday operations. He wanted his schools to be community centers, more or less.

“I started opening up the schools at night, and I did that for all my schools,” said Freeman. “A school is the center of a community, so why close it? I had it open for volleyball, for basketball, for parent nights, for whatever would bring people in.”

As a principal, his goal for students remained much the same as it was when he was teaching.

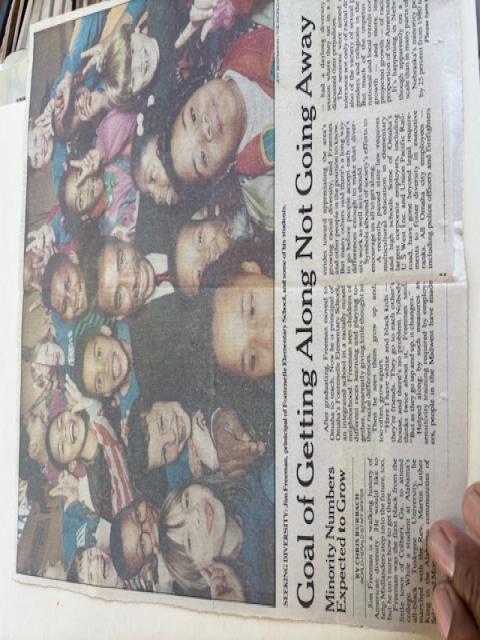

“I wanted them to think about where they started and how much they’d grown throughout the school year, and to be able to carry that on to the next grade level,” Freeman said. “I was always sad when they left, so I wanted to make sure that I had made a difference in their lives. The most important thing for me was for the kids to grow every year.”

The rewards, Freeman often told his teachers through the years, come down the road. That’s the thing about education. It takes patience, and foresight.

“Most people will tell you, ‘All I want is respect. I don’t care whether they like me or not, as long as he respects me,’ but I did care,” Freeman said. “I wanted the kids to like me, because I could get more out of them if they liked me. Now, I wasn’t always going to treat the kids like friends, because I was their teacher or their principal, but I wanted them all to be friends with me.”

The years passed, and Mr. Freeman’s name became synonymous with school in north and northwest Omaha. He won't admit it, but the native Georgian became an OPS legend, revered most of all for how he treats everyone around him.

He hired teachers who possessed the skills to help kids be successful. Most had skills that exceeded his own, and that was okay. Freeman didn't have an ego. He gave them complete trust. He kept relationships at a premium and helped with hundreds of shoestring knots along the way.

At Prairie Wind in the mid-90s, just before he retired from the principalship and started recruiting teachers for OPS, Mr. Freeman was a celebrity in the hallways, always smiling and handing out the world’s best high-fives.

“When I look back on my life, I was so blessed to be able to teach, to be in education,” said Freeman, who was hired by UNO in 2003 and spent the final 16 years of his fascinating career on 60th and Dodge. “I was able to build relationships with so many different people. There’s not a day that goes by where I don’t get an email or a Facebook message or a letter from a former student. It’s just unbelievable, and all of them have stories.”

Their memories are his memories, too.

“I wouldn’t change a thing,” Freeman said. “It was all a blessing. I’ve always thought that I came here to Omaha for a reason, to be the best that I could be and to help other people be the best they can be. Being able to have a positive impact in a student’s life is so important to me.”

It’s a sunny Tuesday in Omaha, and Mr. Freeman and I pay for our lunch, hop in our cars, and drive over to Prairie Wind Elementary. We park, walk down a small hill and pose for a photograph not too far from where that field day was held in May of 1996, when my principal knelt down and helped me with the Hercules of shoestring knots.

I don’t remember how many gold medals I won, but I remember that.

"We used to be here," Mr. Freeman says. "How about that?"

All I have to do is close my eyes.